Even before President Trump’s global chaos-inducing, norm-shattering second term got underway, there was always a necessity for an economically unified Africa. Our arbitrary borders have always presented a difficulty to growth, so in keeping with this week’s theme of Africa’s response to a changing world, here again is a case for the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

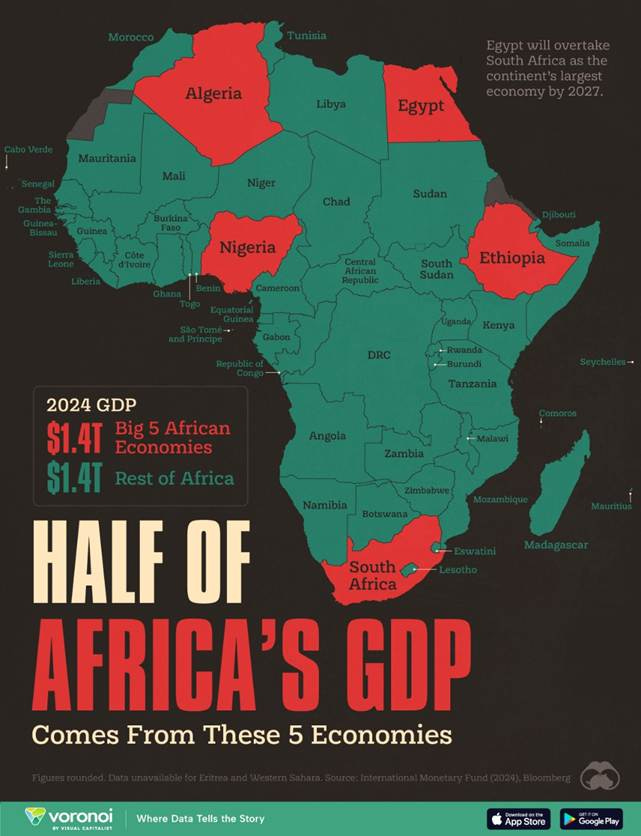

There is a seductiveness about speaking of a singular “Africa” and describing it in aggregate statistics. These overarching statistics cover structural and functional weaknesses that slow economic growth and hamper capital formation. We remain an economic laggard compared to other regions, making us excessively vulnerable to shifts like the ones happening in the world today. There is the fact that five economies account for 50% of the combined GDP of the continent.[i]

Image from the Visual Capitalist

That shows up in our middle class numbers. The AfDB calculated Africa’s middle class to be about 34% of the population but classified as middle class people living on $2 to $20 a day. “By the AFDB definition, Africa’s middle class encompasses three distinct categories: the floating class living on $2-$4 per day, the lower-middle class living on $4-$10 per day, and the upper-middle class on $10-$20 per day…”[ii] The bulk of the African middle class is thus that insecure group called the “floating class”. It is simply too small, disaggregated and vulnerable to drive the economic growth the continent desperately needs.

Let’s take look at a proxy for disposable income in our digital world: Netflix subscriptions. Africa, with its population of 1.37 billion, has a total of $1.8 million subscribers. Latin America, for example, has 53 million subscribers. Again, the “Africa”, here is doing the heavy lifting since South Africa alone accounts for 73% of total subscribers with Nigeria and Kenya rounding out at 10.5 and 3.9 respectively. Leaving the rest of the continent with a paltry 12.3%.[iii] This is a very crude measure of wealth, especially because there are other options. It is, however, a potent indicator of the economic weakness of the continent, a weakness that is compounded by its Balkanization.

At a meeting with the German Ministry of the Economy and Climate, staff covering sub-Saharan Africa noted that German OEMs were excited about the prospect of the AfCFTA, because it would present a market size worth the investment. The small and fragmented market presents challenges that are not commensurate with the returns. In conversations with the Federation of German Industries (BDI), we were told that after almost a decade of a focus on “moving into Africa”, there was not much appetite for the market because of its size and hurdles.

Their perception is not without merit. There are 22 African countries (about 40% of the AU) which are classified as landlocked developing countries or small island developing states.[iv] With this classification comes significant economic challenges: high transport costs, small isolated markets that discourage investors, erode any competitive edge and limit growth.[v] Unlike their landlocked European counterparts like Hungary, Czech Republic, Moldova or Slovakia, landlocked countries in Africa border other poor countries. Against this backdrop, it is important to see why advice like “learn from China or be like Vietnam” is pablum, these are tiny domestic markets where weak systems, predation by the state, weak or non-existent infrastructure impose still higher costs.

Even as the world became more interconnected with the development of global value chains, many of the continent’s economies have struggled to integrate outside of supplying raw materials. An IMF report concluded a decade ago:

“Despite strong growth in trade flows, sub-Saharan Africa’s trade has barely kept pace with the expansion of global trade, even as other regions managed to increase their weight in the global trade network over the same period. Indeed, even after accounting for lower levels of income and economic size, generally longer distances between countries, and a large number of landlocked countries, levels of trade flows emanating from sub-Saharan Africa are found to be only half the magnitude of those experienced elsewhere in the world.”[vi]

Africa’s path to any prosperity has thus always been via the collective – an intentional lowering of barriers, integration of processes, systems and regulation that convert its current weaknesses into strengths – leveraging its combined consumer and business spending to create an attractive market for investment. Everyone acknowledges this is a desired outcome. Now comes the how.

The Cost of Integration:

Integration will come with significant benefits, and at great cost. Competitive firms in South Africa, Morocco, Egypt and Tunisia will present a formidable challenge to incumbents in smaller markets. Greater access to capital in more developed markets would allow actors from there acquire valued assets in smaller markets, sparking resentment from locals about the loss of economic and political sovereignty. Europe’s experience with integration should be an instructive example. Designing integration around its inevitable creative destruction, so that the losers are compensated sufficiently is something I would rather leave to the experts.

For this piece, the focus is on coordination costs, because Africans have largely balked at these substantial costs. In organizational economics, coordination costs rise with the size of the firm. There is no reason why the equation should be different from multilateral institutions that attempt to perform the role of the state at the regional level, without the advantages of the state. There is therefore a desire for an optimal size that reaps the benefit of low adaptation and coordination costs. For our context, the path lay with our Regional Economic Communities. In the search for optimal firm size, “the greater the variability the smaller the optimal size”.[vii] While this is not a like for like comparison, it makes intuitive sense that the coordination cost of integration within ECOWAS, the EAC or SADC would be lower than at the continental level. The two-track process inevitably leads to redundant and duplicative efforts – but there is simply no way around this.

During the Brexit debate, Tony Blair argued that, "In this world, if the medium-size [countries] aren't banding together, the giants are going to sit on us." The giants have been sitting on Africa for a while and if medium-sized European countries need to band together to project strength – what more about Africa?

Collective regional action, whether through economic communities or defense alliances require the presence of a hegemon who bears a disproportionate share of the coordination costs. Angela Merkel’s Germany explained its admission of a million migrants in 2015 as a move to preserve the European Union. During that period, Italy, Greece, Romania and Hungary began considering imposing borders within the EU, a path that would have led to an erosion of the union. For defense arrangement, let’s take NATO where over the last eight decades, the United States has borne the lion’s share defense spending. It thus seems odd that the AfCFTA remains an orphan, no regional power has adopted it. The expectation that a technocratic secretariat is enough to mold the entire continent into an economic unit, when similar efforts have repeatedly stalled at the sub-regional level, is wishful thinking.

Economic integration is a political decision. I have not seen the necessary political support for the project. I am particularly focused on South Africa and Nigeria as drivers here. It is possible that South Africa has provided support to its national, who heads the AfCFTA secretariat. Any such support must be very subtle – maybe a tad too subtle for what is essentially a political project. To the outsider, South Africa does not seem to be expending any political capital to drive the project. When nations push their citizens as heads of regional projects, one would hope it would go beyond the psychic benefit of having your citizen in that role but would include support for the institution’s objectives. Since there is not a singular hegemon on the continent – this project will stall and sputter to death without the overt political buy-in of the continent’s largest economies. It means expending serious political and economic capital to coax and drag laggards across the finish line. These larger economies will have to cover the direct costs of integration – from concessions to holdouts, to defraying the cost of attending coordination meetings.

One can understand Nigeria’s hesitation- the argument that the economy isn’t ready. One imagines local importers and incipient manufacturers are not looking forward to competing with better developed competitors from elsewhere. It would thus be logical for them to lobby the federal government to slow-walk the project. But successful export oriented economies became successful not simply by choosing winners and protecting incumbents – they imposed export discipline on them. While the current Nigerian economy may work for a few, it is not designed to deliver large-scale benefits to its large and growing population.

In South Africa, access to European, American and Chinese markets have been enough to justify its passing interest in the greater African economy. In a fragmenting world where market access is wielded as an instrument of foreign policy, it is suboptimal to neglect regional markets.[viii] In the most developed markets, intra-regional trade accounts for a majority of their world trade. In Europe, for example, “intra-regional merchandise trade represented 65% of Europe’s world trade in 2022, the highest amongst the major world regions. The lowest was for Africa (14% in 2022, down from 16% in 2018).”[ix] It also seems suspicious that Africans who claim that the continent is the “future” are not responding to their own claims with conviction. If African consumption will drive future global growth, it would make sense to establish first-mover’s advantage there now.

My last post focused on fundamental changes to the world as we know it. Across Europe, there is a clear trend of a rightward shift in politics. “…Over the past 15 years hard-right parties have made substantial gains across the region.”[x] With their nativist stance, many have made migration the centerpiece of their political platforms. Not unlike President Trump’s “America First” movement, these rightwing parties are inward looking. Africa’s inability to fully develop a regional market and increase intra-regional trade would ultimately leave it at the mercy of these political trends. If there were ever impetus required to drive through the AfCFTA and invest in regional infrastructure, it would be now.

[i] https://www.visualcapitalist.com/mapped-just-five-countries-make-up-half-of-africas-gdp/

[ii] https://www.un.org/osaa/sites/www.un.org.osaa/files/ads2023_policy_brief_2.pdf

[iii] https://emergingmarkets.today/africa-prefers-showmax-subscription-numbers-surpass-netflix/

[iv] https://www.uneca.org/stories/afcfta-poised-to-revive-economies-of-landlocked-developing-countries-and-small-island

[v] https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/statements/african-least-developed-and-landlocked-developing-countries-building

[vi] https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/dp/2016/afr1602.pdf

[vii] https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-015-8658-0_7

[viii] https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2023/01/11/Geo-Economic-Fragmentation-and-the-Future-of-Multilateralism-527266

[ix] https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/wtsr_2023_e.pdf

[x] https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2025/02/28/hard-right-parties-are-now-europes-most-popular

Excellent points